12 Bayesian Workflow

In the previous sections, we discussed a range of non-inferential tasks essential for a successful Bayesian analysis, such as diagnosing the quality of sampling methods, assessing model assumptions, comparing models, and more. Drawing an analogy to Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), which is used to understand data, we can view these tasks as part of an Exploratory Analysis of Bayesian Models. This involves exploring the models, their relationship with the data, and the resulting outcomes. Recognising the need for tasks beyond pure inference is a cornerstone of modern Bayesian analysis. However, we can take this further by acknowledging that these tasks are interconnected within a broader Bayesian workflow (Gelman et al. 2020).

Applying Bayesian inference to real-world problems demands not only statistical expertise, subject-matter knowledge, and programming skills but also an acute awareness of the decisions made throughout the data analysis process. These interrelated components form a complex workflow encompassing iterative model building, model checking, validation, troubleshooting computational issues, understanding models, and comparing them.

We can think of a Bayesian Workflow in a very abstract way as a graph with infinite nodes and edges representing all the potential alternatives we could take when analysing all the potential datasets. In this sense, there is “THE” Bayesian workflow and for any concrete analysis we only explore a few realizations from it. Alternatively, we can think of a myriad of Bayesian workflows, and thus we should talk about “A” Bayesian workflow. In any way, we are faced with potentially many instances that are context-dependent and we can not concretely talk about any of them without knowing the details of a particular analysis. But what we can do is to discuss some of the elements we should take into account, like we already did in previous chapters. And then provide some guidelines and general recommendations about how to proceed.

The methods, tools, and practices for Bayesian analysis will improve over time. As technology advances, we expect automation through software tools, and this guide will evolve accordingly.

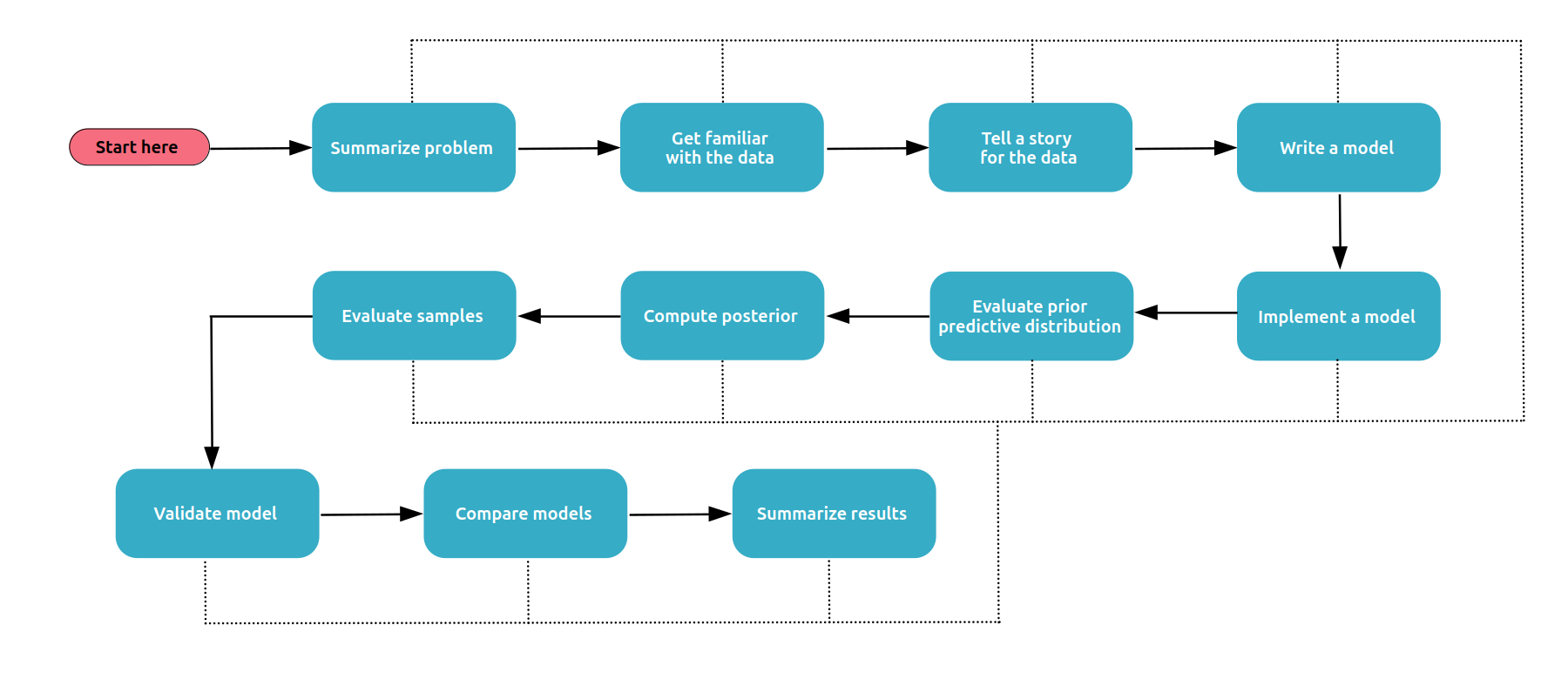

12.1 A picture of a Bayesian Workflow

Figure 12.1 shows a simplified Bayesian workflow (Martin, Kumar, and Lao 2021), check the Bayesian Workflow paper for a more detailed representation (Gelman et al. 2020). As you see there are many steps. We need all these steps because models are just lucubrations of our mind with no guarantee of helping us understand the data. We need to first be able to build such a model and then check its usefulness, and if not useful enough keep working, or sometimes stop trying. You may also have noticed the “evaluate samples” step. We need this because we, usually, use computational methods to solve Bayesian models, and here again we have no guarantee these methods always return the correct result (see Chapter 4 for details).

Designing a suitable model for a given data analysis task usually requires a mix of statistical expertise, domain knowledge, understanding of computational tools, and perseverance. Rarely a modelling effort is a one-shot process, instead, typically we need to iteratively write, test, and refine models. If you are familiar with writing code, then you already know what we are talking about. Even very short programs require some trial and error. Usually, you need to test it, debug it, and refine it, and sometimes try alternative approaches. The same is true for statistical models, especially when we use code to write and solve them.

12.2 A Blueprint for Effective Bayesian Workflows

Often, especially for newcomers, Bayesian analysis can be overwhelming. In this section, we have collected a series of tips and recommendations so you can get a quick reference. Here we write the recommendations linearly, but in practice, you may need to come back one or more steps and sometimes skip steps. Think of these notes, not as a partiture of a classical piece that a violinist aims at playing almost exactly, but as the musical score that a Jazz bassist follows, you are free to improvise, rearrange some parts, and omit others, and you can even add your notes!

12.2.1 Summarize the problem

Summarize the key points of your problem, and what you would like to learn from the data. Think also about others, what your boss, client, or colleague would like to find out or learn. This does not need to be super thorough, you can revisit goals later, but they can help you organize your modelling efforts and avoid excessive wandering.

Sometimes you will not have any clear idea of what to expect or what to do, your only expectation will be to get something useful from a dataset, and that’s fine. But other times you may even know what kind of model you want, perhaps your boss explicitly asked you to run this or that analysis. If you already know what kind of problem you want to solve, but are not very familiar with the approach, search for what methods, metrics or visualizations are common for that problem/data, and ask others for advice. This is more important the less familiar you are with that type of problem/data. If you are familiar, then you may already know which methods, visualizations, and summaries you want to use or obtain. Either way write an outline, a roadmap to help you keep focus, and later to track what you have already tried.

12.2.2 Get familiar with the data

It is always a good idea to perform Exploratory Data Analysis on your data. Blindly modelling your data leads you to all sorts of problems. Taking a look first will save you time and may provide useful ideas. Sometimes it saves you from having to write a Bayesian model at all, perhaps the answer is a scatter plot! In the early stages, a quick dirty plot could be enough but try to be organized as you may need to refer to these plots later on during the modelling or presentation phases.

When exploring the data we want to make sure, we get a really good understanding of it. How to achieve this can vary a lot from dataset to dataset and from analysis to analysis. But there are useful sanity checks that we usually do, like checking for missing values, or errors in the data. Are the data types correct? Are all the values that should be numbers, numbers (usually integers or floats) or they are strings? Which variables are categorical? Which ones are continuous? At this stage, you may need to do some cleaning of your data. This will save you time in the future.

Usually, we would like to also do some plots, histograms, boxplots, scatter plots, etc. Numerical summaries are also useful, like the mean, and median, for all your data, or by grouping the data, etc.

12.2.3 Tell a story for the data

It is often helpful to think about how the data could have been generated. This is usually called the data-generating process or data-generating mechanism. We don’t need to find out the True mechanism, many times we just need to think about plausible scenarios.

Make drawings, and try to be very schematic, doodles and geometrical figures should be enough unless you are a good sketcher. This step can be tricky, so let us use an example. Let’s say you are studying the water levels of a lake, think about what makes the water increase; rain, rivers, etc, and what makes it decrease; evaporation, animals drinking water, energy production, etc. Try to think which elements may be relevant and which could be negligible. Use as much context as you have for your problem. If you feel you don’t have enough context, write down questions and find out who knows.

Try to keep it simple but not simpler. For instance, a mechanism could be “Pigs’ weight increases the more corn they are fed”, that’s a good mechanism if all you need to predict are your earnings from selling pigs. But it will be an over-simplistic mechanism if you are studying intestine absorption at the cellular level.

If you can think of alternative stories and you don’t know how to decide which one is better. Don’t worry, list them all! Maybe we can use the data to decide!

12.2.4 Write a model

Try to translate the data-generating mechanism into a model. If you feel comfortable with math, use that. If you prefer a visual representation like a graphical model, use that. If you like code, then go for it. Incomplete models are fine as a first step. For instance, if you use code, feel free to use pseudo code or add comments to signal missing elements as you think about the model. You can refine it later. A common blocker is trying to do too much too soon.

Try to start simple, don’t use hierarchies, keep prior 1D (instead of multivariate), skip interactions for linear models, etc. If for some reason you come first with a complex model, that’s ok, but you may want to save it for later use, and try with a simplified version.

Sometimes you may be able to use a standard textbook model or something you saw on a blog post or a talk. It is common that for certain problems people tend to use certain “default” models. That may be a good start, or your final model. Keep things simple, unless you need something else.

This is a good step to think about your priors (see Chapter 10 for details), not only which family are you going to use, but what specific parameters. If you don’t have a clue just use some vague prior. But if you have some information, use it. Try to encode very general information, like this parameter can not be negative, or this parameter is likely to be smaller than this, or within this range. Look for the low-hanging fruit, usually that will be enough. The exception will be when you have enough good quality information to define a very precise prior, but even then, that’s something you can add later.

12.2.5 Implement the model

Write the model in a probabilistic programming language. If you used code in the previous example the line between this step and the previous one, may be diffuse, that’s fine. Try to keep the model simple at first, we can add more layers later as we keep iteration through this workflow. Starting simple usually saves you time in the long run. Simple models are easier to debug and debugging one issue at a time is generally less frustrating than having to fix several issues before our model even runs.

Once you have a model, check that the model compiles and/or runs without error. When debugging a model, especially at an earlier stage of the workflow, you may want to reduce the number of tuning and sampling steps, at the beginning a crude posterior approximation is usually enough. Sometimes, it may also be a good idea to reduce the size of the dataset. For large datasets setting aside 50 or 90% of the data could help iterate faster and catch errors earlier. A potential downside is that you may miss the necessary data to uncover some relevant pattern but it could be ok at the very beginning when most of the time is spent fixing simple mistakes or getting familiar with the problem.

12.2.6 Evaluate prior predictive distribution

It is usually a good idea to generate data from the prior predictive distribution and compare that to your prior knowledge (mikkola_2023?). Is the bulk of the simulated distribution in a reasonable range? Are there any extreme values? Use reference values as a guide. Reference values are empirical data or historical observations, usually, they will be minimum, maximum or expected values. Avoid comparing with the observed data, as that can lead to issues if you are not careful enough (see Chapter 10 for details).

12.2.7 Compute posterior

There are many ways to compute the posterior, in this document, we have assumed the use of MCMC methods as they are the most general and commonly used methods to estimate the posterior in modern Bayesian analysis.

12.2.8 Evaluate samples

When using MCMC methods, we need to check that the samples are good enough. For this, we need to compute diagnostics such as \(\hat R\) (r-hat) and effective sample size (ESS). And evaluate plots such as trace plots and rank plots. We can be more tolerant with diagnostics at the early stages of the workflow, for instance, an \(\hat R\) of 1.1 is acceptable. At the same time, very bad diagnostics could be a signal of a problem with our model(s). We discuss these steps in detail in Chapter 4.

12.2.9 Validate the model

There are many ways to validate your model, like a posterior predictive check, Bayesian p-values, residual analysis, and recovery parameters from synthetic data (or the most costly simulated-based calibration). Or a combination of all of this. Sometimes you may be able to use a holdout set to evaluate the predictive performance of your model. The main goal here is to find if the model is good enough for your purpose and what limitations the model can have. All models will have limitations, but some limitations may be irrelevant in the context of your analysis, some may be worth removing by improving the models, and others are simply worth knowing they are there. We discuss these steps in detail in Chapter 4.

12.2.10 Compare models

If you manage to get more than one model (usually a good idea), you may need to define which one you would like to keep (assuming you only need one). To compare models you can use cross-validation and/or information criteria. But you can also use the results from the previous step (model validation). Sometimes we compare models to keep a single model, model comparison can also help us to better understand a model, its strengths and its limitations, and it can also be a motivation to improve a model or try a new one. Model averaging, i.e. combining several models, is usually a simple and effective strategy to improve predictive performance. We discuss these steps in detail in Chapter 7.

12.2.11 Summarize results

Summarize results in a way that helps you reach your goals, did you manage to answer the key questions? Is this something that will convince your boss, your peers or the marketing department? Think of effective ways to show the results. If your audience is very technical do a technical summary, but if your audience only cares about maximizing profit focus on that. Try to use summaries that are easy to understand without hiding valuable details, you don’t want to mislead your audience.